Violence – The Key Social Variable “The key to understanding how societies evolve is to understand the factors that determine the costs and rewards of employing violence.” The Sovereign Individual

“The Sovereign Individual” by James Dale Davidson and Lord William Rees-Mogg originally written in 1997, provides equal parts history and prophecy. The authors predicted a number of social, political and technological developments currently unfolding based upon a thorough historical analysis of what they call the logic of violence (LV). The book argues that controlling violence (ie. Protecting life and property) is the key social variable and that each society forms a logic of violence based upon two factors:

- The returns or profitability of violence,

- The optimal scale of violence (large vs. small)

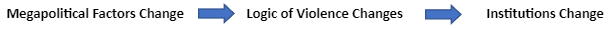

“The Sovereign Individual” explores how historical shifts in megapolitical factors (topography, climate, technology, and microbes) drive changes in the LV. Finally, when the LV shifts, almost everything (institutions, morality, economics) in society adapts to the new logic.

The book argues that history has seen at least three transition periods in the logic of violence; and that the world currently is transitioning from an industrial economy to an information economy. This article highlights two previous transitions examined in the book, namely, dark ages to feudalism and feudalism to the industrial period. Our aim is to use the historical transitions to understand the Sovereign Individual model and then apply the model to the current transition in the LV.

The Sovereign Individual Model

Transition from the Dark Ages into the Feudal Age:

As the dark ages came to a close, circa 1000 AD, the advent of improved technologies provided mounted warriors with new weapons and gear. Donned with armor, spurs and saddles designed for battle, mounted warriors significantly expanded their military advantage over foot soldiers. These warriors, the pre-cursors to knights, leveraged the newfound advantage in violence to raid and pillage farms. Europe turned into a horseback version of “The Roadwarrior” movie. Eventually, the church intervened with the Code of Chivalry in an effort to curb the violence. Until then, mounted warriors were the law of the land.

As reflected above, technology changes in the form of armor, spurs, saddles, increased the profitability of violence because military advantage was consolidated into a relatively few hands. The disparity in effectiveness at violence between mounted warriors and the rest of the populace meant that mounted warriors could leverage their advantage to extract value from everyone else. In other words, the use of violence became a lot more profitable than it had been in the Dark Ages. In order to bring the violence back under control, the Chivalric Code was introduced. Mounted bandits became Knights and were recast as the lowest level of the nobility. In order to maintain their improved social position, knights were expected to behave within certain boundaries. This example provides a great instance in which a society adapted in order to manage violence by introducing institutional and moral system changes.

Castles proved to be another significant megapolitical change during the feudal ages. Castles altered the logic of violence by shifting the advantage strongly to the defender. Attacking a castle proved expensive and risky. The castle owner enjoyed tremendous military advantage over attackers. As a result, the countryside was sliced up into many small fiefs within which a small number of defenders could be effective both against invaders and also at extracting value from local peasant farmers. This example demonstrates that castles shaped the logic of violence in a way that meant military force was best organized locally and at small scale.

The implications of organizing society around small sovereignties were significant. We see that both taxation and military power were concentrated at the bottom of the nobility structure. Military decisions would have been made in a relatively decentralized manner. If the “king” wanted to raise an army, he had to negotiate with a wide variety of supporters. Further, we can see that the feudal system would have been poor and very anti-trade/commerce. Who would have wanted to move goods to a market twenty miles away and be taxed by five different nobles along the way. We can also see why an institution like the church might have grown in power. As a mostly non-military institution, the church was able to act as a social coordinator and rule maker across a wide area when no other organization could. Each of the above social factors are adapted to the framework dictated by the logic of violence. However, when the logic of violence changes, everything adapts to the new reality.

Transition from the Feudal Age to the Industrial era:

By approximately 1500 AD, technological changes were washing away the foundations of feudalism. The invention of gunpowder, for example, enabled an infantry soldier with little training to slay a knight. Cannons, simultaneously, turned castles, the defensive masterpiece of feudalism, into death traps. Attackers no longer needed to storm the castle walls. Attackers could sit back and blast away until the walls turned to rubble. The advantages enjoyed by defenders in the feudal period evaporated. Guns and cannons proved to be expensive however, and were most effectively used and produced at large scale. So, in order to be militarily effective in the industrial age you had to have three things:

- A large population to conscript soldiers from,

- Large centralized production of guns and cannons,

- A big commerce driven tax base to fund numbers one and two (decreasing importance of agriculture).

None of these items could be accomplished at small scale. In effect, the small sovereignties that dominated in the feudal ages lost their military relevance and over time, were rolled up into much larger kingdoms/empires. The optimal scale of violence had shifted from small in the feudal period to large scale in the industrial age.

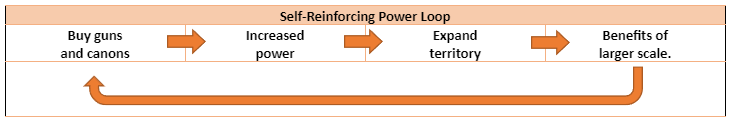

The increased scale of violence also drove an increase in the profitability of violence during the industrial era. As a nation builder with foresight, if you could be among the first to leverage gunpowder weapons, you could build a self-reinforcing loop and perhaps become emperor as demonstrated in the table below. In other words, it was highly profitable for nation builders to roll up neighboring sovereignties into an ever growing empire that then benefit from increased efficiencies of scale.

As the logic of violence shifted during this period, the problems that feudal institutions solved ceased to exist. As a result, new institutions and ways of thinking evolved to better align with the new reality imposed by industrial scale violence.

From Industrial to Information Age:

The world is currently transitioning from the Industrial economy toward an Information economy. Microchips, the internet and encryption are altering the logic of violence in ways that mean violence is no longer optimized at large scale. New technologies allow military effectiveness to be achieved by a single person or a small group. Osama bin Laden, for instance, and his small network in Pakistan proved to be an existential threat to a superpower. One anti-ship missile can sink an aircraft carrier. One anti-aircraft missile can down a $335 million dollar aircraft. So just as the castle lost its relevance in the Industrial age; so too the military tools of the industrial age are losing relevance in the Information Age. The logic of violence is shifting to reduce the returns associated with projecting large scale industrial power.

Nation states capitalized on the increased returns to large scale violence during the industrial age. However, encryption and the internet are moving substantial value creation onto the internet and outside the realm or capability of nation states to extract value. This reality has significant implications for future tax flow streams.

In summary, here are a couple of things the authors say weren’t true in the industrial era but are true in the information economy.

- The cost of projecting power has increased dramatically,

- The profits associated with projecting power are decreasing,

- The scale required to be militarily effective shrank dramatically (danger from one lone hacker),

- Substantial value will be moving behind a non-violent form of defense called encryption which will significantly impacts tax revenue.

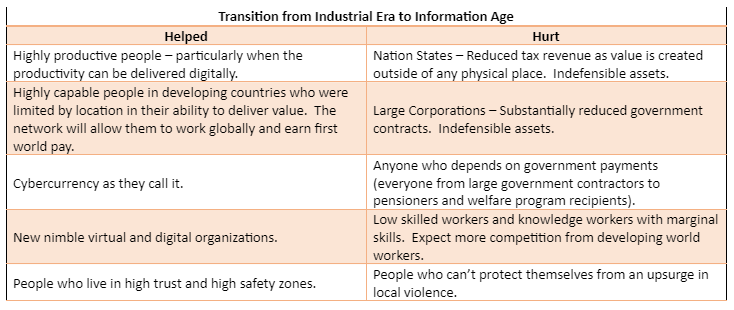

As these new realities become more pervasive, industrial era institutions like nation states and large corporations will wither. The authors point to a number of winners and losers from the decay of industrial era institutions.

As the title of the book implies, the authors see a future in which the winners in the table above become sovereign individuals. These sovereign individuals will experience control over their lives incomprehensible to citizens of nation states. The authors say little about morality, compassion or concern for people on the right side of the table above. Perhaps that is the topic of a different book. Some of those listed on the right side of the table deserve no compassion while others do. What kinds of institutions and moral systems will evolve to address this need?

Large scale = doomed

The above material represents a brief summary of one of the key ideas from “The Sovereign Individual” by James Dale Davidson and Lord William Rees-Mogg. I recommend reading this excellent work. For citations and supporting data see the original text.

Refreshing the SI Perspective

I am studying Balaji Srinivasan’s fantastic new book Network States. It argues that encryption allows people to secure real property rights and that new types of institutions called network unions and network states will emerge. To me, the ideas in “Network States” offers an instance where some of the ideas put forward in SI back in 1997 are finding their way into the real world.

I am learning about network unions and states in a practical way at x20s.com. I posted a number of paid projects there. If you want to learn with me, please visit.